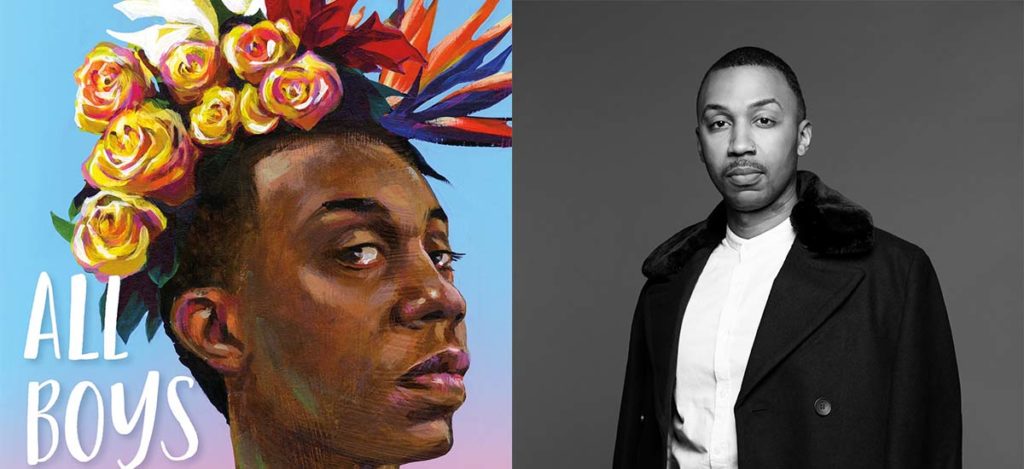

All Assaults Aren’t: A Sexual Assault Awareness Q & A with ‘All Boys Aren’t Blue’ Author George M Johnson

This Sexual Assault Awareness Month, we were exploring the culture that breeds sexual violence among young adults, and particularly among queer and trans youth of color, with author George M. Johnson.

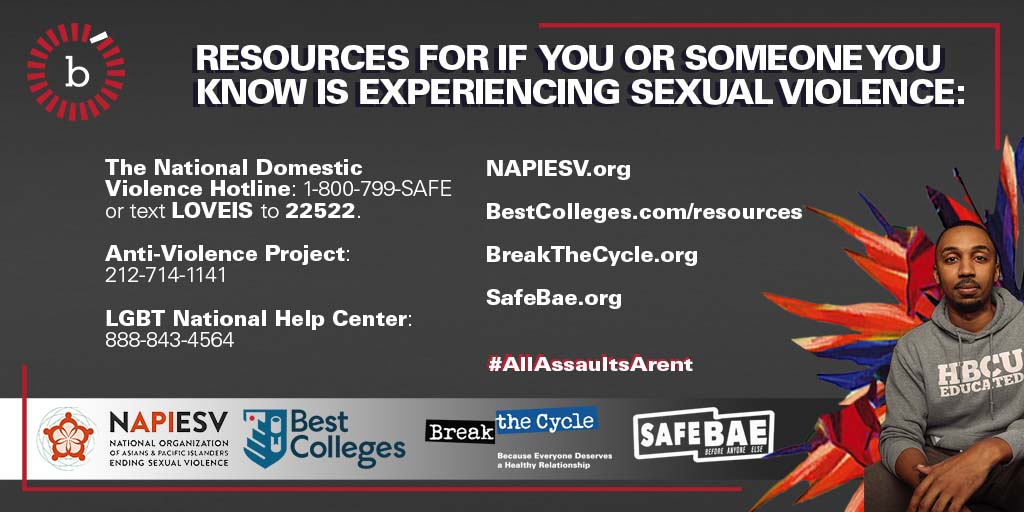

Johnson’s stunning new young adult memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue tackles many of the less explicit ways a cisheteropatriarchal culture leads to sexual assault. We invited him to join us and our partners Break the Cycle, SafeBae and the National Organization of Asians and Pacific Islanders Ending Sexual Violence on our ALL ASSAULTS AREN’T… campaign to highlight the ways sexual violence might be experienced differently than what is often portrayed in popular media, especially in the time of the pandemic.

The goal was to encourage audiences to recognize and act to change norms that perpetuate sexual violence, and we incorporated aspects of our previous campaign, Ring the Bell, which had the same goal in regards to intimate partner violence.

ALL ASSAULTS AREN’T… consisted of a weekly reading guide for Johnson’s book (included at the bottom of this post), a Twitter town hall, and a weekly Q&A.

We’ve compiled all of our questions and Johnson’s full answers from the Q&A below:

How might COVID-19 add to the lack of resources and feeling of unsafety for people experiencing sexual violence, and what they should do?

George Johnson: Unfortunately COVID-19 is forcing many who are living in abusive households to be forced into confinement with one another. There has already been reporting that domestic violence numbers are up and since the self-isolations began. And although there are no numbers on sexual assault, we know that this pattern will likely play out in the same way.

The first suggestion is that if there is anywhere else you can stay and self isolate to do so. Whether it be at another family member’s home or a friend’s home, the best thing you can do is think about your safety in the moment.

GJ: If that is not an option, there are hotlines and agencies that are still operating during this time with the understanding and potential resources available to get you out of the unsafe situation.

A final option is that it might be time to tell someone you are being abused. Circumstances like this sometimes put us between a rock and a hard place leaving us with minimal options available. However, this may be the time to confront the fear that comes with naming your abuser, telling your truth and finding that trustworthy person to report it too.

In the chapter “Boys will be boys”, you discusses molestation at the hands of his cousin, and the difficulty of balancing personal trauma with feeling the need to protect your harm-doer when they are close to you. If you are sexually assaulted and feel guilt, shame or indifference afterwards, what can you do to process those feelings?

GJ: The first step for me was to come to a realization that I had no fault in what was done to me. This was not something that happened overnight and in fact took a lot of years for me to process. I can honestly say that my process started with finally feeling comfortable enough with a person I felt I could trust to finally say what happened.

Saying what happened to me was a type of healing I didn’t know I needed. It was a release of so much pinned up emotion that it was almost uncontrollable when it occurred. However, that release also involved me letting go of a lot of the guilt and shame I had felt.

I would say a lot of my guilt was wrapped up in the fact that I felt I could’ve done something to prevent it and the fact that part of me was struggling with my identity and sexuality to the point that I thought being queer was synonymous with being a bad thing. Much like how people will call young girls “fast” or “grown” but coddle young men while raising them to believe their manhood is attached to sexual conquest.

The processing of those feelings is one that is personal and only on your timetable. Don’t pressure yourself to “get past” anything. The best thing you can do for yourself is acknowledge your trauma, and begin to work on what accountability for your abuser looks like, but most important what healing looks like for you in the now, and long term.

In the same chapter, you also explore how you were close to this cousin, not only relationship-wise, but also in age. How do you have a conversation about assault with your family, when your harm-doer is also a member of your family?

GJ: This can be a hard conversation for several reasons. The first being that when a family member violates your trust it is easy to project that violation of trust to everyone, especially other members of your family. I think the most important thing is acknowledging the hurt from the trust being broken and beginning the healing process as you determine who is best to tell.

If you feel that you can talk to your parents or guardian and the environment will be safe where you feel supported, then I advise that is who you tell first. However, I also know that many don’t have this as an option. That is when you start to look to other family members, an aunt, an older cousin that you feel you can trust this information with and will put your truth first over that of your abuser.

In my case, I told a friend first. In telling my friend, it eventually gave me the courage to tell one of my cousins and slowly start talking to other family members about it. Although it was many years after it occurred, it was still freeing to be able to talk openly about what happened and honestly something I wish I had done many years ago.

I always say that safety has to be at the forefront of your mind whenever you decide to tell your truth because it is most important that you are here. So even if you can’t immediately go to family, you can always start with the best friend and maybe the adult in their home bringing it to the adults in your home. A teacher as well. It’s about your comfort in that moment.

In the chapter “Losing my virginity twice”, you discuss how painful it was to have penetrative sex for the first time. Because you initially consented, you felt you had to just deal with the pain. Why might you feel like you can’t rescind consent?

GJ: I honestly don’t think we are taught how. People think a “yes” means until the task is completed which is completely false and a dangerous way of thinking. You have the right to give someone consent and the right to rescind that consent based on what is best for you. Never feel shamed for “changing your mind,” as people often try to guilt others using that term as if it’s the same thing as making a poor decision.

In my case, I was 21 years old and it was my first time engaging in penetrative sex where I was being penetrated. Because of the lack of education I had around sex, I assumed that the initial engagement in intercourse would be painful. I wasn’t thinking about my own health and safety as much as I felt obligated to please my partner. Sex is taught to us as an action that has an “ending” but we must rethink that.

Sex is something that can be stopped at any time. There is no rule that you must finish sex after consent is initially given. Furthermore, no one has the right to continue engaging in sex with you after you have rescinded consent.

In the chapter “Boys will be boys”, you discuss how you knew having sexual interactions with your cousin was wrong, although your body felt something “right.” How do you reconcile the feelings of your body responding one way to sexual contact while your mind is responding differently?

GJ: It’s tough because it honestly feels like your mind is playing a trick on you. Your body can easily have natural reactions to sex even though you are in an unsafe environment or being assaulted. There is no need to feel any guilt or shame because your body did something that your mind wasn’t fully in control of during a situation you feel you are being violated in.

The most important thing to know is that your body’s response does not equal consent. Your body responding to a sexual assault does not negate that you were sexually assaulted. Our bodies do many things to protect us as does our mind, as safety is often at the forefront when we are under attack.

All Boys Aren’t Blue is out NOW! Order here

ALL BOYS AREN’T BLUE READING GUIDE: