A Black woman navigates outrage over continued anti-Black state violence alongside the pandemic’s mental health challenges

*This piece is published in partnership with Black Youth Project as part of By & For: Black Youth, a written series documenting the issues affecting Black girls and gender non-conforming youth.

By Gloria Oladipo

“If I have to self-isolate, I’m nervous I may kill myself.” I remember saying this nonchalantly to a friend of mine as we both watched Coronavirus ensnare the world. I had already predicted a dip in my mental health, particularly at the thought of being forced to self-isolate for 14 days or quarantine in toxic environments. My study abroad program was cancelled and the coordinators were aggressively evicting us from our housing, lest England go on lockdown.

However, while I correctly predicted that COVID would hurt my mental health, I didn’t realize how racialized the mental health emergency would be or how fragile my life would feel.

Mandated isolation combined with the stress of a global pandemic have driven many of us into deep depressions, intense panic attacks, and other signs of mental unwellness. Unfortunately, the mental health emergency that many of us are experiencing remains unaddressed. Furthemore, for Black people, COVID-19 has brought on a whole other dimension of pain as we bear witness to anti-Blackness.

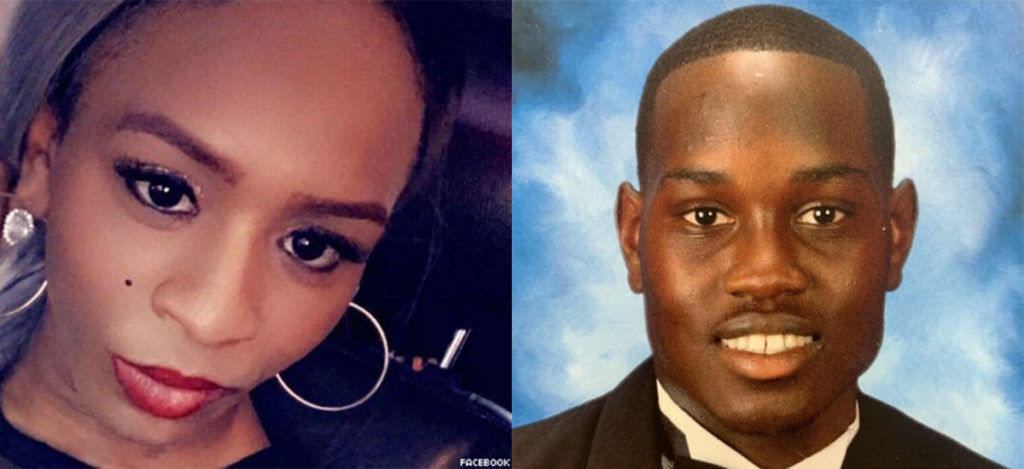

For one, an onslaught of Black people have been murdered by the police state this year. Their deaths have been making the rounds on social media, as activists, celebrities, “concerned citizens” and the like repost and reshare hashtags and photos. Ahmaud Arbery’s murder was accompanied by a triggering video. Nina Pop, a 28 year old Black, trans woman, was murdered back in February with almost no coverage or attention brought to her death.

We have been grieving as a community for so long already, as white supremacy produces more Black corpses year after year. Now, we are forced to bear witness as the world “rediscovers” that Black lives don’t matter to white supremacy. Having to constantly see people who look like us—who could be us—dying is too much. Especially in quarantine, when social media can be the closest thing to connection.

Secondly, COVID-19 has been particularly hard on Black communities, despite being heralded by white people as the “great equalizer.” In Chicago, a city where Black people makeup only 30.1% of the population, 72% of COVID deaths are Black people. In Georgia, where Black people account for 32.4% of the population, we make up more than 80% of COVID hospitalizations.

Not to mention that these cases and deaths have been blamed on us; we have been told by health departments that our own inability to follow stay-at-home orders and our “bad” diets is to blame. We are being gaslit by government officials, who lecture us to stay at home for our “Big Mama,” as if we are ignorant, selfish people who don’t care about our family.

Law enforcement is also being weaponized against us. While white people in affluent areas of New York City enjoy a relaxing, unmasked day at the park, Black people are tackled in the street by police. Even internationally, Black people are seen as a shorthand for disease; in China, there are increasing reports of Black people being discriminated against, thrown out of restaurants and evicted from their homes. Both domestically and abroad, Black people are being seen as incubators of COVID and treated as such.

Finally, for so many Black people, being quarantined in our home invites a new level of intrusion from white folx. Work-from-home and online schooling means the same codeswitching that I do in “professional” settings follows me home. The gaze of white folx, the one that Black people constantly have to negotiate to be “professional” enough in work and school settings, follows us into our bedrooms, living rooms, and wherever else we are forced to have Zoom meetings. My home has been infiltrated by the racial dynamics that I already try to escape at work and school. I feel watched and judged, even as I attempt to relax and restart in my own home.

The quarantine has meant unique stressors for Black people on top of the mental stress that others are going through. Unfortunately, while there has been a litany of mental health resources to help people cope with the quarantine, there has been a stark silence in popular media about how Black people should cope with being targeted and having to grieve for each other and ourselves.

How are we supposed to simultaneously hold outrage over the constant murders of Black people while also navigating the new mental health challenges that quarantine brings? Ultimately, that relies on community care.

We have to love ourselves and each other in a way that white society never will. We have to prioritize our mental health above all else, especially as new challenges are brought up daily. For me, this means being in community with other Black folx: people to laugh with, grieve with, scream with, and have other cathartic experiences.

I used to think that sitting on social media and continually inhaling and exhaling and inhaling Black death would make me feel more “informed” or propel me to action. In reality, and during this time especially, I needed to draw hard boundaries and give myself permission to feel and to distance when needed.

And, sometimes, even that isn’t enough. Even the ways in which I carefully plan my mental wellness—taking my medication, sprinkling in a well-needed crying break—isn’t enough. And during those times, it all comes down to doing whatever it takes to make it until tomorrow without feeling like white supremacy has won, without feeling like living is in vain just because if the police kill me, I will be a trending hashtag who sinks to the bottom of everyone’s memories.

There isn’t a single answer about how to cope with racialized mental health struggles. Simple “self-care” tips are offensive in the face of the grief and pain Black people go through. But I think it’s about honoring our feelings and healing the very best we can—collectively and individually. I think it just boils down to how to get as many of us here until tomorrow, doing whatever it takes to make tomorrow feel like an option when so few Black people are given that choice.

To continue the conversation on mental health in the pandemic, join our upcoming events:

Gloria Oladipo is a 20 year old Black woman and a 3rd year Cornell student. She is a freelance writer with pieces at Teen Vogue, Healthline, Black Youth Project, Rewire Magazine, and more. Moreover, she is also a regular contributor at Wear Your Voice magazine. She enjoys writing about all things race, gender, politics, mental health, pop culture, and more. In her free time, she enjoys reading, gardening, and working on her non-freelance based creative projects. You can learn more about her on her Instagram (@glorels) or her Twitter (@gaoladipo).