A Look Back at Representation in 2020: 8 Ways Black Hair Matters

How Will We Continue This Fight in 2021?

By, Lauren Stockmon Brown

*This piece is published as part of By & For: Black Youth, a written series documenting the issues affecting Black girls and gender non-conforming youth.

Today, Black women are loving their hair unapologetically. We are creating and buying our own products from brands made “By and for Us.” Black hair is a story of resilience and the story has continued as a key topic of conversation throughout 2020. Yes, our twist outs, fros and low cuts are taking center stage as a representation of independence and strength. And yet, centuries of race-based hair discrimination has sparked the saying, “Black hair is not just hair.” Why?

Historically and in modern times, the texture of Black hair is used as a tool to alienate and incapacitate the Black community. During the 17th and 18th century, Black people were forced into captivity and their hair was shaved to drive a loss of identity. Headwraps were given to Black women to signify poverty and inferiority. Tignon Laws were built to enforce a social status and a caste system based on lighter skin tones and straighter hair. And still, miraculously and relentlessly, we continue to prevail.

This rich history is just one of the reasons why we celebrate our natural kinks, curls, and styles today. In 2020, we saw many companies and brands join the conversation by supporting this “new” standard of beauty that fights to uplift rather than to divide. However, this wave of “representation matters” is not a novel strategy for advertising and branding at all. In fact, in 2007, writer and curator Susannah Walker released her book, Style & Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women (1920-1975). Throughout her piece, Walker discusses the symbolic history of the afro throughout American history. She explains how the “Black is Beautiful” movement began the outward rejection of white beauty standards. For example, advocates of the Black Power movement encouraged Black women to stop straightening their hair and buying cosmetics that would lighten their natural skin tones.

Walker highlights the ways in which the Black is Beautiful movement provided Black women with a variety of styles that were realistically more attainable with Black hair types. These styles were not only more attainable, but also healthier for our hair. Walker even references Angela Davis as one of the leading revolutionaries who sported an afro in the early 1960s. She takes a deep dive into how Davis chooses to wear an afro as a political statement and an ongoing act of resistance in the 70s, 80s and beyond. Davis states, however, that this is an example of how the public turned her afro into “politics of fashion” rather than “politics of liberation.”

Walker goes on to discuss the complexities of identity politics as she references the ways in which terms like “Black is beautiful” were used to make Blackness profitable. At the time, many companies who were white owned worked to embrace the “soul market” (the Black market) as they changed their advertising to be directed at the Black community. Just last June, the international responses to the killing of George Floyd began as civil unrest and protests sparked a more sustained movement than prior demonstrations. A global conversation erupted as modern day companies scrambled to claim “diversity” and attempted to avoid being less relevant or even “cancelled”.

Davis’ choice to wear an afro — and the commercial exploitation of the hairstyle in subsequent years — is a prime example of how Black hair is consistently politicized and manipulated throughout history. For better or for worse, Black hair is a form of self-expression that continues to show up prominently in our everyday life, politics and various forms of entertainment like fashion magazines, Netflix movies, Tik Toks and countless media trends.

In the wake of last summer’s social justice uprising, America was given a chance to engage in a “racial reckoning.” However, this country’s response to equality has barely begun. By delicately shining a light on “racial equity” through marketable taglines, products and holiday gift guides — it has become easier to lull ourselves into thinking we’ve reached a point of true progress.

Was 2020 the second wave of the “Black is Beautiful” movement? Or just more exploitation of Black culture for advertising and profit? The following examples will show you the first steps towards properly celebrating Black hair and Black culture in mainstream media in 2020 and how we have a chance to do better in 2021 and beyond.

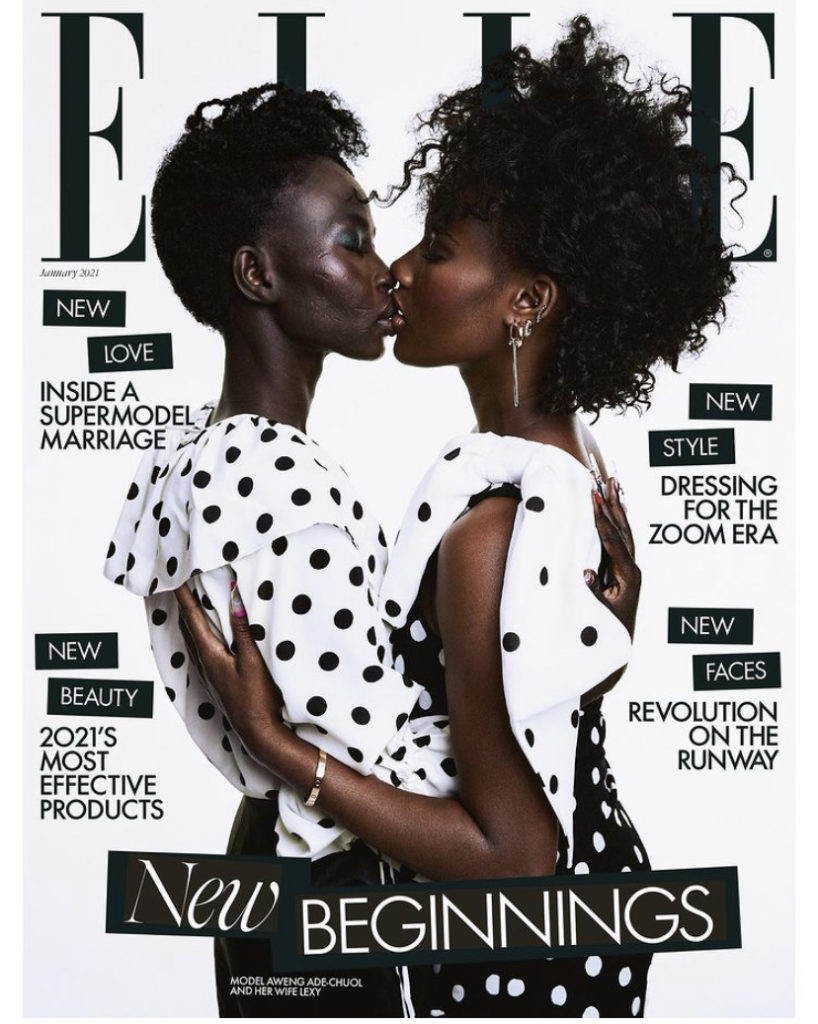

1. Elle UK, January 2021 Issue: “New Beginnings” (released December 1st, 2020)

Elle UK, a “fashion,” “feminist” and “beauty” magazine features Aweng Chuol (left), a “South Sudanese supermodel who went from a refugee camp to billboards around the world,” and her wife Alexus (right) on the cover of their January 2021 issue. The cover showcases paint splattered phrases across the page, “New beauty. “New love.” “New faces.” “New beginnings.” “Revolution on the runway.” Elle UK provides an inside scoop into a supermodel marriage. Two Black and queer women rocking their natural hairstyles, lightly kissing on the front of a global publication. Perhaps in future issues, Aweng’s love for Lexy will be considered less “revolutionary” and more common. While Elle UK’s choice to showcase a Black queer relationship will no longer be an act of rebellion and moreso a glimpse into accepted variations of love.

More Info: https://www.elle.com/uk/life-and-culture/culture/a34805600/aweng-january-cover-interview/?utm_campaign=likeshopme&utm_term=www.instagram.com/p/CINVXmuhGkf/&utm_medium=social&utm_source=instagram&utm_content=po

Photo: ELLE UK Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CINVXmuhGkf/

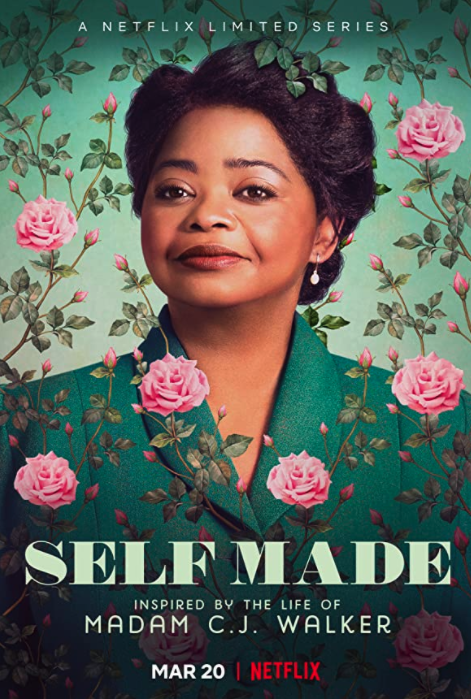

2. Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker, Netflix Miniseries

Streaming services like Netflix are highlighting their library of Black content beyond the critically acclaimed “When They See Us” (2019) by Ava DuVernay. More than 31 million households worldwide watched this miniseries about the 1989 Central Park Five case in its first four weeks of release. As of this year, on June 10, Netflix showcased their collection of 56 films, documentaries and TV shows including Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J Walker and starring Octavia Spencer. A fictionalized depiction of untold stories centering pioneers of Black hair care and documenting the hostile trek Walker faced when becoming America’s first Black and female millionaire in 1913.

Photo: IMDB, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8771910/?ref_=ttmi_tt

3. The Official Campaign of the CROWN Act

The CROWN Act is the first of its kind. It is a form of litigation that passed at the state level in the United States to prohibit discrimination based on hair texture and hair style. This legislation confronts the denial of employment and educational opportunities because of protective hairstyles including twists, locs, braids or bantu knots. Black people are disproportionately faced with practices that target them in public spaces, including the workplace. As a result, Black women are 1.5% more likely to be sent home or know of a Black woman sent home from work because of her hair. To date, seven states have passed the Crown Act, nine states have filed or pre-filed, fourteen states have filed but did not pass, and a total of twenty states have not filed or passed the Crown Act.

Photo: Official CROWN Act Campaign Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/B8y9x5Qgagx/

4. New York Times: “Black Women Learn to Braid While Social Distancing”

Just last March, the New York Times covered a story about Black women learning how to braid while social distancing. Similar to the rest of the world, Niani Barracks has acclimated to COVID circumstances and moved her once in-person salon to online. With nonessential businesses closing, Ms. Barracks made the creative choice to lead classes on Facebook Live and teach other Black women how to braid while salons and barbershops were closed for an indefinite amount of time. One of Ms. Barracks students, Debra Turbboe, told the NYT that many participants don’t know how to take care of their own hair. This step-by-step process is one of the many ways Black hair has created a sense of community amidst a global pandemic.

Photo: Nappy.Co, https://www.nappy.co/photo/1832

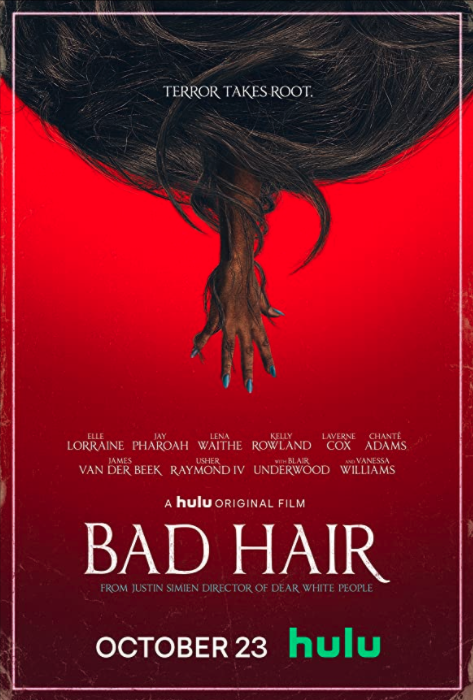

5. ‘Bad Hair’ (2020), Hulu Film

Bad Hair is a 2020 American satirical comedy horror thriller film written, directed and produced by Justin Simien. It received moderately positive reviews from critics. According to Vulture, “Bad Hair” is a satirical “love letter to Black women and the unparalleled power they possess to endure and persevere.” Unfortunately, this film is said to be “geared toward the understanding of white folks.” Though (thankfully), the film stars Black female and queer leads like Vanessa Williams, Kelly Rowland and Laverne Cox. It takes place in 1989 and documents how an ambitious young professional gets a weave in an effort to assimilate into the image-obsessed world of music and television. The story’s plot unravels as the protagonist’s hair takes on a mind of its own and Anna’s seemingly flourishing career comes to a sudden halt. It’s a story of growth, loss and reckoning. If not for its cinematic structuring, the film is applauded for its primarily Black and female casts and how it creates space for complex characters of color to exist in a fictionalized world.

Photo: IMDB, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4798836/?ref_=tt_mv_close

6. Affirmative Power of Politicians Wearing Natural Hair Styles

It’s no secret that Black women are consistently policed for their hair styles and body image. Though, politicians like Stacey Abrams are adding to a reclamation of self within and outside of the Black community. In 2007 through 2017, Abrams served as a minority leader in the Georgia House of Representatives. Currently, she is best known for her voting rights activism throughout the 2020 election period. Ultimately, Abrams is a powerhouse,, and we can finally start to see a reflection of our own twists and curls in electoral politics and in government. There is an affirmative power in representation. Though, it is important to emphasize that Abrams’ brilliance certainly surpasses the texture of her hair.

More Info: https://theglowup.theroot.com/black-hair-matters-the-affirmative-power-of-politician-1830750951

Photo: Stacey Abrams Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CHSw_ujh_dG/

7. New York Times: “Black L.G.B.T. New Yorkers are using social media to find barbershops that double as safe spaces.”

According to writer Aaron Randle, “Over generations, barbershops have become so culturally integral to Black communities that they have been the setting of a blockbuster movie franchise, the focus of rigorous academic study, the stage for popular music videos and comedy skits and, most recently, the backdrop for an HBO talk show from the N.B.A. superstar LeBron James.” Randle dives into questions of race and gender and how these topics intersect with sexuality in a way that transcends heteronormative safe spaces for Black people. Including traditionally “therapeutic” spaces like a hair salon or barber shop. In other words, the Black barbershop is not always a safe space for LGBTQIIA+ Black people, as it can be hyper-masculine, heteronormative and at times, homophobic. Though, Randle highlights how social media has become a valuable tool for Brooklyn barbershop owner Khane Kutzwell. Through the use of social media, Ms. Kutzwell, who identifies as queer, connects with her customers and caters to the intersectionality of the Black community by providing a barbershop that welcomes the LGBTQIIA+ community in ways that hair salons and barbershops in the Black community historically have not.

More Info: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/nyregion/nyc-queer-black-barbershops.html

Photo: Unsplash, https://unsplash.com/photos/WbEibGKHBMY

8. NBC News: “Opinion| US Open Women’s Final Features Naomi Osaka’s Masks, Black hair and a Bold Cultural Statement.”

During this year’s US Open, NBC News wrote an opinion piece explaining why Naomi Osaka’s “bold, beautiful Black hair matters” in the “bright white tennis world.” Similar to Serena Williams, Osaka is coaxed into an ongoing conversation about her curly hair and whether or not it’s respectful to wear it naturally in a professional match. As a society, we must continue to question why we even need to discuss a pro athletes hair texture in general? As the conversation seems distracting, and ultimately irrelevant to her talents. The 23 year-old Grand Slam singles champion and winner of the US Open, also uses her platform to lead conversations on social advocacy and sports activism.

Photo: Naomi Osaka Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/CFDlD2YpoCN/

These examples are signs of cultural growth. But, how will we continue this fight in 2021? America is slowly beginning to create space for Black people to exist as authentic and complex individuals, but the work is far from over. In the grand scheme of media representation, we tend to lack discipline and genuity. So, our word-choice and the topics we choose to question are an important part of pushing against societal benchmarks of “desirability.” As this year begins, remember that these examples are only springboards for effective forms of media representation, and that true progress stems from the simple, yet difficult choice to allow yourself and others the space to express their individuality.

Lauren Stockmon Brown is a passionate storyteller and writer who focuses on race, gender, mental health and politics. She is a Fulbright Scholar and founder of the “My Colorful Nana” Project, a collected group of “Generous Thinkers” and a podcast series that encourages listeners to celebrate their individual definitions of the words “beauty,” “femininity,” and cultural identity. Learn more about her work and journey on “My Colorful Nana” on Instagram & Twitter.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I love this article, it’s incredibly inciteful, informative, and interesting. Additionally, I believe that this is the kind of writing that a white audience could greatly benefit from in terms of cultural education as well as ethnic awareness.